Rochester Community Schools has a proud history of affirming and protecting students’ right to read. Banned Book Week is a good time for them to live up to it.

by Gayle Martin

It’s Banned Book Week 2022, and to kick it off, PEN America released a chilling report, “Banned in the USA: The Growing Movement to Censor Books in Schools” on Monday. The comprehensive report details not just how book banning efforts in schools have skyrocketed in the last year–currently affecting “nearly 4 million students” nationwide– but also how the nature of these new efforts are different from what we have seen in the past. Instead of being initiated by a few concerned parents, PEN America found “the large majority of book bans underway today are not spontaneous, organic expressions of citizen concern. Rather, they reflect the work of a growing number of advocacy organizations that have made demanding censorship of certain books and ideas in schools part of their mission.”

Michigan had the sixth highest number of book bans in the US with 41 reported bans in 4 different districts. One of those districts is Rochester Community Schools. Six of those banned books were taken from RCS libraries. Over 15,000 of those 4 million students affected live here. In Rochester.

Read that paragraph again.

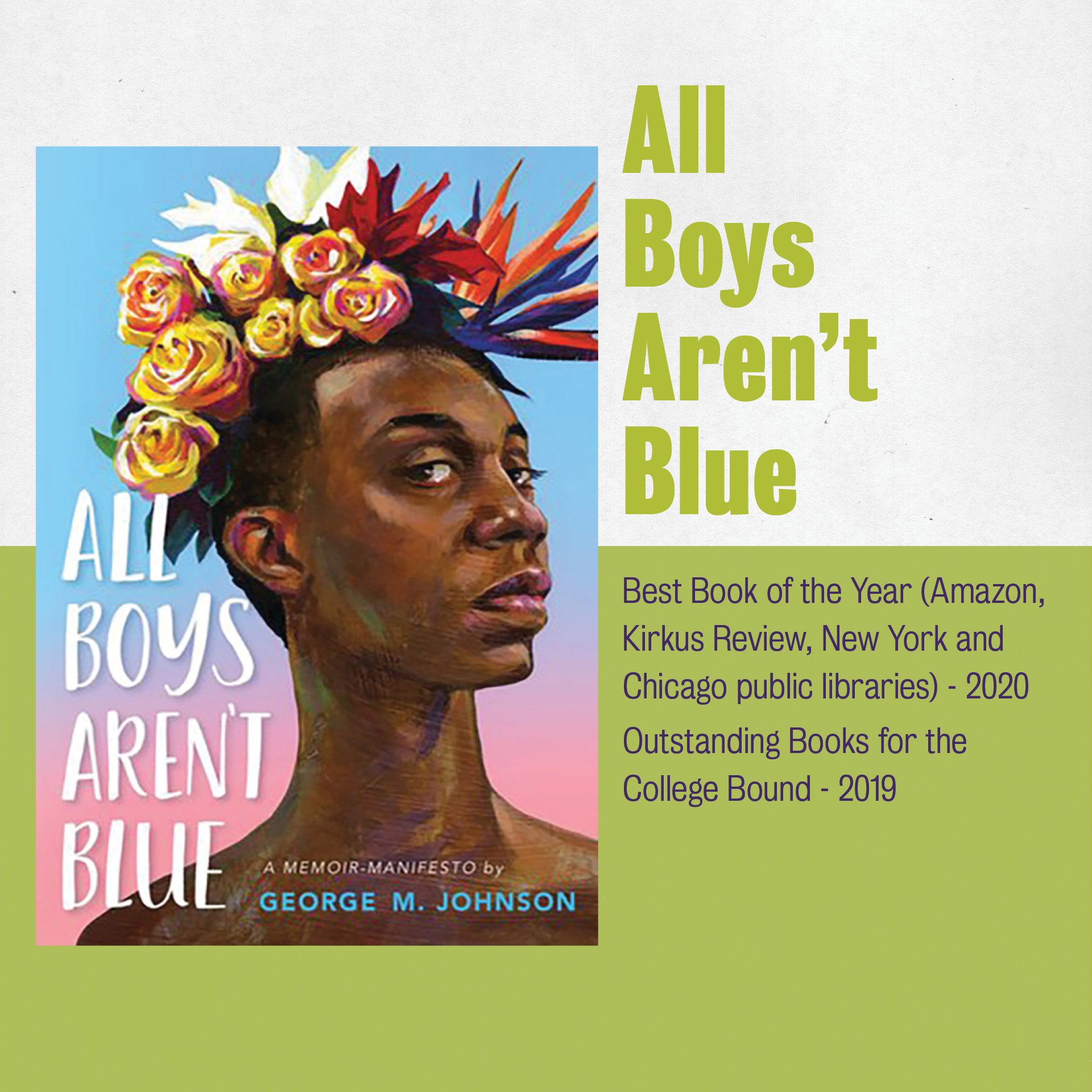

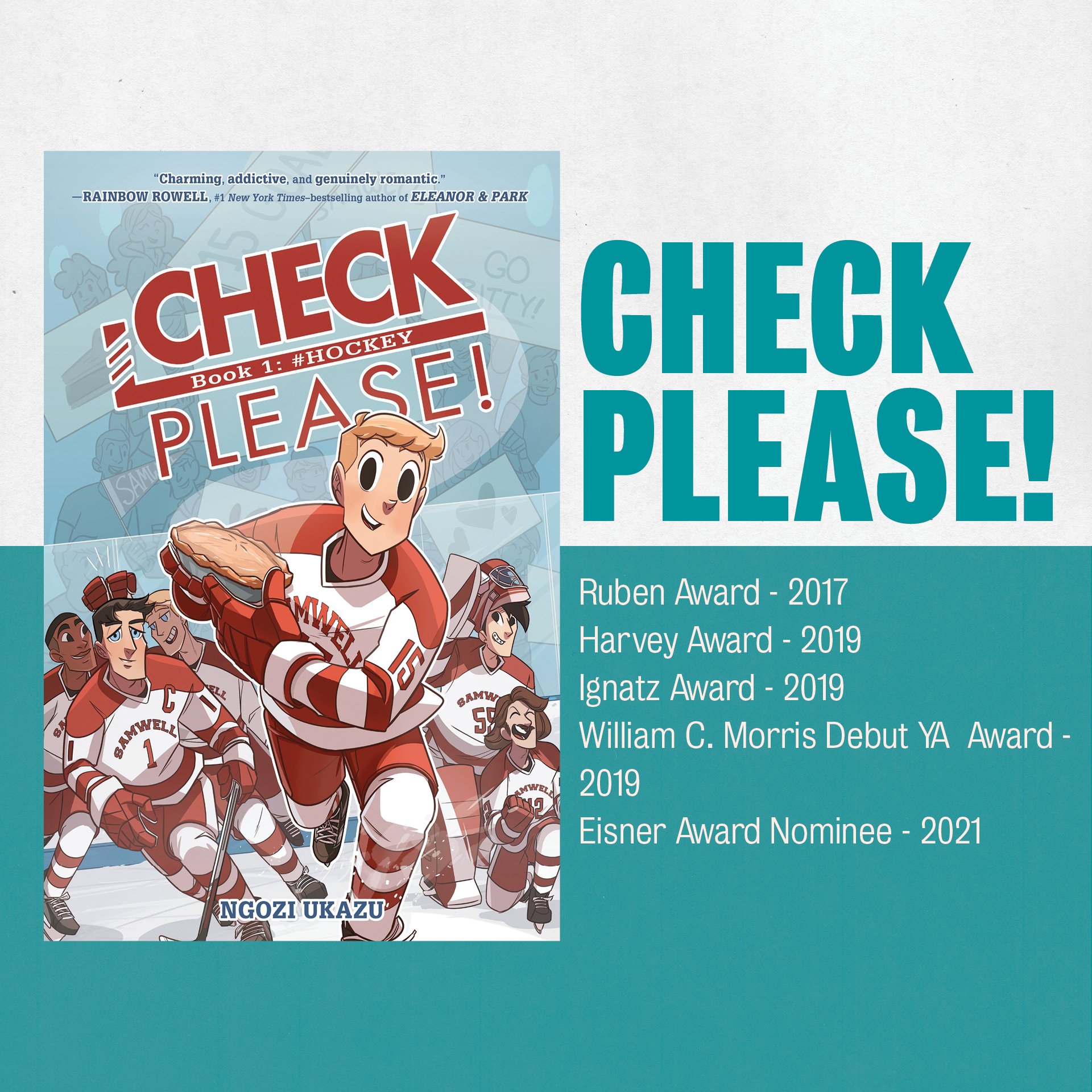

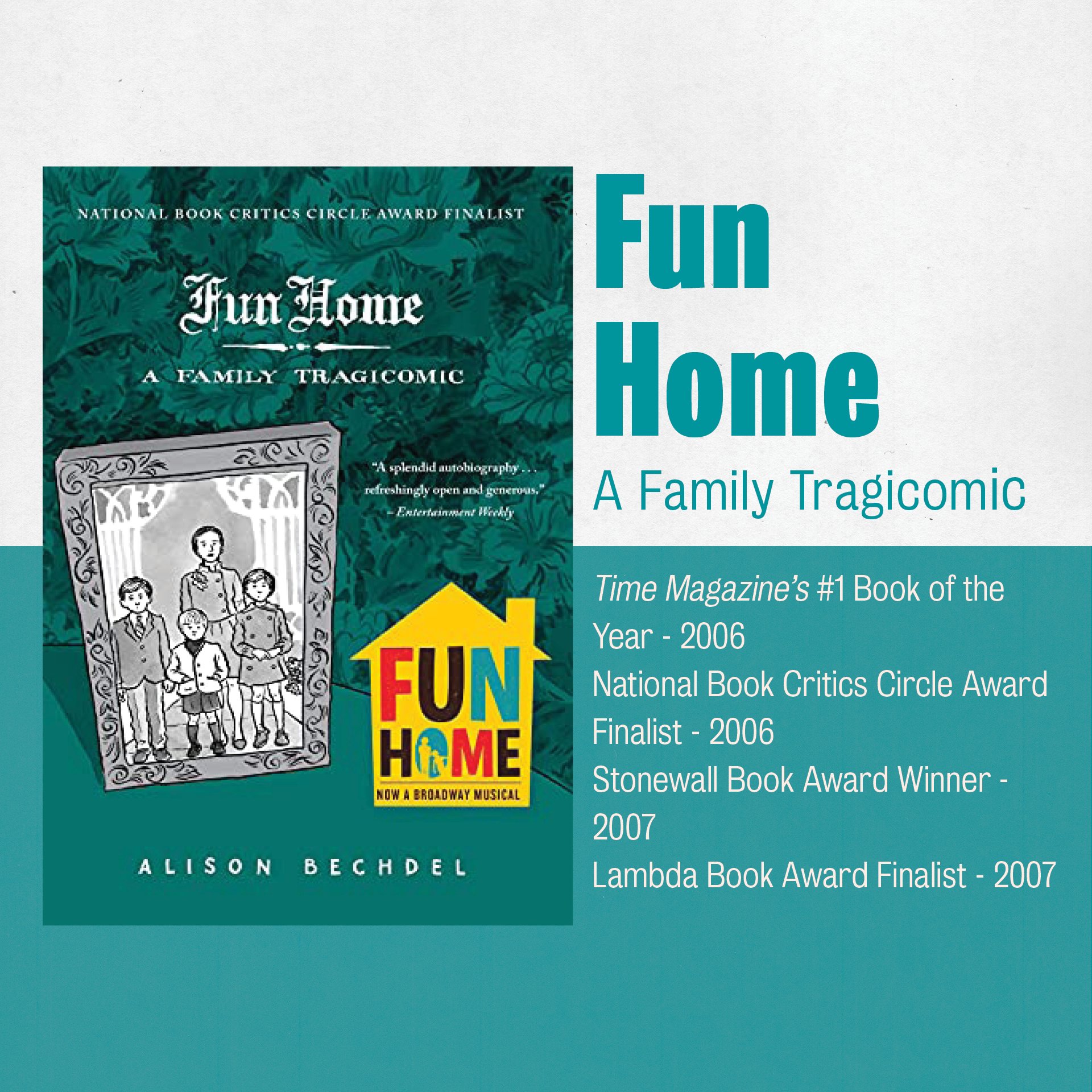

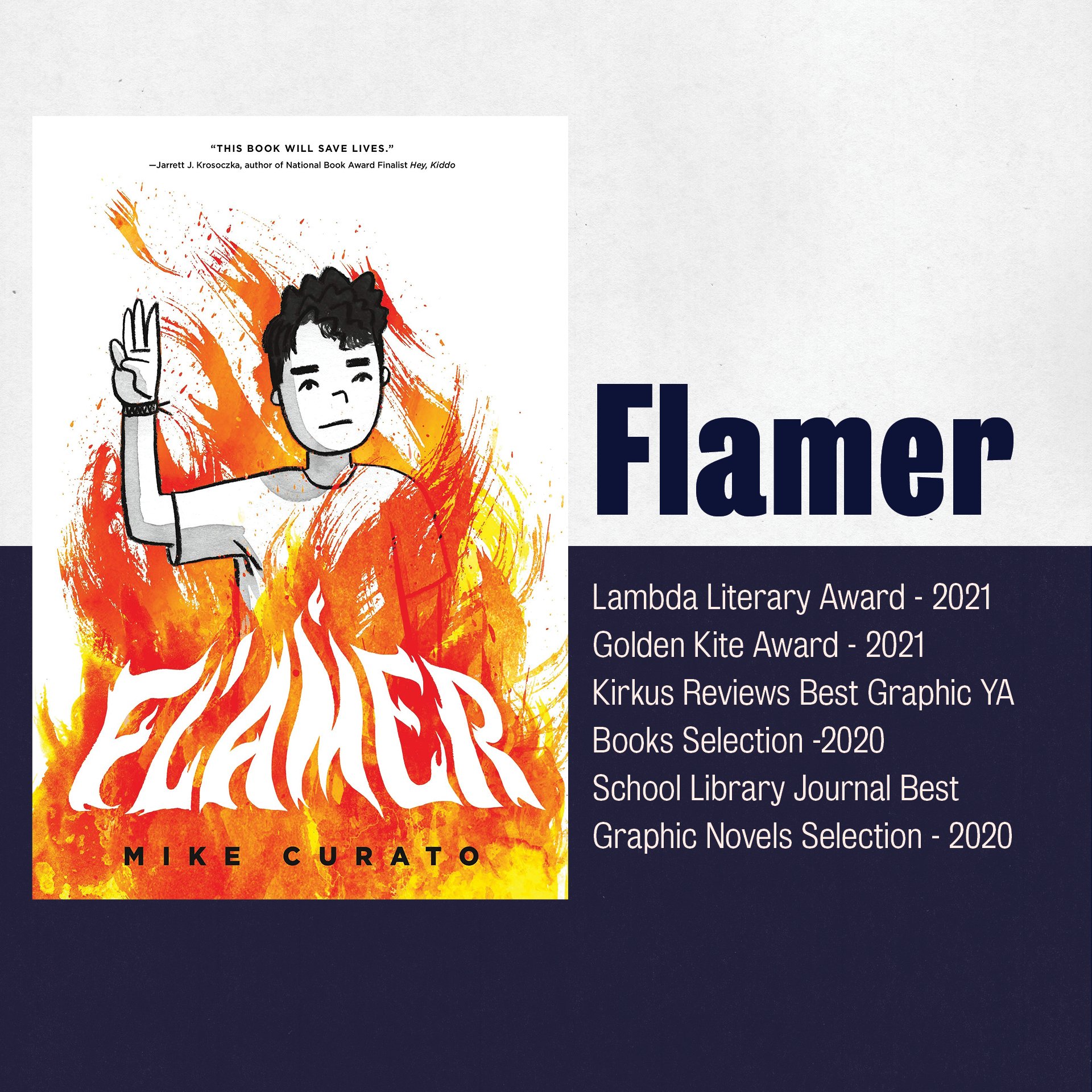

In February last year, six books were removed from the high school libraries, supposedly because the material review committee needed them to read. (See the infographic for a complete timeline.) According to the American Library Association (ALA), that is not supposed to happen. Books are supposed to remain on library shelves while being reviewed. And according to PEN America, any removal of books by a school official is a ban. Yes. A ban.

Moreover, seven months later, we are still in limbo as to the books’ permanent fate. The review was finished before the end of last school year, but the district has not made public the conclusions of the review. And the books have not been returned to the libraries. Whether this is because of some misguided impulse on the administration’s part to avoid negative publicity, or whether it is because of an unwillingness to stand up to the political pressure of a few loud voices, it is unacceptable. Banned Book Week would be a perfect time to announce the decision.

Hopefully, that decision will reflect the history of our district.

Todd v. Rochester Community Schools, 1972

One of the (many) ironies of the book challenges in our district is that I have heard a few people who are in favor of the challenges say that they just want RCS to be the well-respected district it once was, the one they remember attending as a student, or the one they moved to the area to be a part of.

I don’t know what RCS they are thinking of, but the one I know has a history of supporting students’ right to read and to access information–including Michigan case law history.

In March 1971, Rochester Schools was sued by a parent because a high school literature elective his 16-year-old was enrolled in was teaching the novel Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut (Todd v. Rochester Community Schools). The parent alleged that since the novel included characters that expressed views that were critical of Christianity, teaching it was a violation of the First and Fourteenth Amendment, specifically, the establishment clause.

In the initial trial, the Presiding Judge found for the plaintiff, Mr. Todd. The judge not only agreed that teaching the book was a violation of the separation of church and state, but also seemed to be heavily influenced by what the judge called vulgar and “obscene” content, even though the plaintiff never claimed the book was “obscene.” The judge ordered RCS to stop teaching the book and also ordered that it should be “banned from the library” temporarily. (Interestingly in regard to the current book challenges in RCS which have only sought–so far–to remove library books, the judge stipulated that after a period of time when the book was no longer being promoted or recommended by the school, it could be reintroduced to the library, presumably so that it would be available to individual students who chose to read it. Even the judge who thought the book was obscene and was fine with removing it from the classroom did not think it was appropriate for it to be permanently removed from the library!)

RCS appealed that ruling.The Appellate Court reversed the lower court’s decision, and this decision is still the precedent and still considered a landmark case in school censorship.

First, the Appeals Court dealt with the trial judge’s references to obscenity, pointing out that obscenity was not mentioned in the suit, and, even if it were, it did not meet the legal definition of obscenity. Next, they addressed the heart of the case–the inclusion of religious themes and of characters with negative views of Christianity in the book. On this question, the court found, essentially, that the mere inclusion of religion or expression of religious views in a book does not mean that the school is either “advancing” or “inhibiting” those views. In other words, inclusion is not indoctrination.

The court pointed out, “If plaintiff's contention was correct, then public school students could no longer marvel at Sir Galahad's saintly quest for the Holy Grail, nor be introduced to the dangers of Hitler's Mein Kampf nor read the mellifluous poetry of John Milton and John Donne. Unhappily, Robin Hood would be forced to forage without Friar Tuck and Shakespeare would have to delete Shylock from The Merchant of Venice. Is this to be the state of our law? Our Constitution does not command ignorance; on the contrary, it assures the people that the state may not relegate them to such a status and guarantees to all the precious and unfettered freedom of pursuing one's own intellectual pleasures in one's own personal way.”

In the summary of the case, the court also resoundingly affirmed everyone’s right to read:

“One of the reasons that our constitutions have wisely precluded sovereign interference with an individual’s right to read, think, speak, observe, and pray as he desires is the fact that these concepts are so arbitrary and diverse that they are foreign to standardization and any possible test of right-wrong. Government has no legitimate interest in controlling or tabulating the human mind nor the fuel that feeds it.”

My experience in Rochester Schools

The Todd case was settled almost two decades before I started working in RCS, but all of my experience in the district confirms the district’s historical commitment to the freedom to read.

I hired in to teach eighth grade English at Van Hoosen Middle School in February 1988. I had a classroom library from then until the day I retired in June 2018. I freely recommended and lent books to students from my library for 30 years. No administrator ever questioned what books I had in the library. Moreover, no parent ever questioned what books I had in the library. It never crossed my mind that they would. Both the administration and the parents largely trusted me and all teachers to make professional decisions and be responsible stewards concerning their students’ reading.

Throughout most of my career, teachers expected that they would have the discretion to choose not only which books they could keep in classroom libraries, but also that they would be the primary selectors of what books would be purchased for full-class use in the curriculum. I sat on too many curriculum committees to even count over the course of my career and often was tasked with choosing texts as part of writing or revising curriculum. I never remember one text that I or a committee asked for that was denied, unless it was because the school/district didn’t have the funds to make the purchase. Nor do I remember parents objecting to any book we chose, including books that are frequently targets of book banners.

One example is the book Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson, a book that is frequently challenged even today. In the early 2000s, the English department at Stoney Creek decided to add it to the list of books that teachers could choose to teach in LA9. I only taught LA9 for a few years after we adopted the book, but it was always a big hit with my students and I personally never had a parent question it. I know that a few other teachers did have a very small number of parents request an alternate reading for their child. And, of course, the teachers always complied. The book was never challenged district-wide.

That continued even after 2005 when one parent did come to a board meeting to challenge another book, Push by Sapphire. The parent was upset that this title was included on a list of independent reading books handed out to juniors in one class. As far as I know, no physical copy of the book was actually in the school. The challenge was reviewed, but since there was no book to remove from anywhere, the only “resolution” of the challenge was that all English teachers were required to list the titles of the books they taught in class on their syllabus (which I’m pretty sure most already did) and also add a brief description of each book (which was new).

At least every teacher I know at Stoney Creek complied with this directive for years–-resulting in pretty much no response from parents yet again. Since I did a lot of independent reading in my classes and would recommend books and let kids check out books from my library freely, to comply with the spirit of directive, I even included these two options for parents on my syllabus and asked them to choose one: They were comfortable with their child choosing their own books, or they wanted to approve all of their child’s book choices. In the four or five years I did this with a hundred or so tenth graders each semester, I don’t think I even had five parents who requested to approve all of their child’s book choices.

None of these experiences are as strong of a defense of the right to read on the part of the school as the Todd case is, of course. But they do show that historically–even back in some “good ol’ days” when the district was somehow so much better than it is now to some people–the administration and the school board and the parent community generally trusted the classroom teachers specifically and schools overall. Historically, any controversies over books or ELA curriculum have been extremely rare and have settled quickly without removing any books.

Where do we stand now?

Unfortunately, the events of the past year or so have put a black mark on RCS’s history of protecting students’ First Amendment rights and their right to read. When the books were removed from the libraries last February, RCS became a district that bans books. That is forever now part of its history, too.

It is easy to understand that administrators may have been initially flustered or intimidated by the loud, angry voices calling for the books to be removed or by the political pressure they were under. It is easy to understand that, not having dealt with a situation like that before, they may not have known the right thing to do. It is easy to understand administrators making an honest mistake when they initially removed the books.

But it is not easy to understand at all why we have not been informed of the decision the district has made or why some or all of the books have not been returned to the shelves. I can think of only a few possible reasons for this. Either the district has decided to permanently ban the books but doesn’t want to advertise this because of fear of public outrage. Or the district has decided to retain the books but doesn’t want to advertise this because of fear of public outrage. Or the district has decided to retain the books, but rogue administrators have not returned them to library shelves because of fear of public outrage.

Parents and citizens on both sides of this issue deserve to know the decision. The issue is not going to go away and the district is going to have to confront some angry people whatever they do.

Banned Book Week is the perfect time for the district to step into the spotlight and let everyone know: Are we going to return to being a district that supports the First Amendment and follows the legal precedent that we ourselves helped set fifty years ago? Or are we now a district that bans books?

More about the books challenged in RCS: